The Rise of National-Populism in the Philippines

- jmlane8

- Apr 3, 2021

- 26 min read

How "Duterte Harry" Breaks from the Norm

By J. M. Lane

Abstract

There is a growing trend throughout the globe that has far-reaching impacts on every country in the modern world. Growing income inequality, fear of globalization, and a growing disconnect between the average person and those in power has led to the rise of national-populism. Rodrigo Duterte, well known for his human rights violations and outspoken tone on the world stage, has tremendous popularity in the Philippines. While he reflects a larger movement globally, Duterte is a unique phenomenon that is purely Philippine in nature. Understanding the history of the Philippines, it is easy to see what led to the rise of a national-populist. However, why is Duterte so different than other national-populist leaders in the Philippines and around the world? The purpose of this study is to explore the reasons behind the rise of Duterte, applying two common theories to the circumstances that led to his election. Results show that geography may have had a larger role than previously thought.

Introduction

The rise of Rodrigo Duterte on the international stage has been anything but dull. His hardline stance against drug dealers and especially China’s encroachment in the South China Sea has brought unwanted attention to the Philippines in recent years. His popularity with the electorate has led many people to question the effectiveness of Filipino democracy (Rauhala, 2016). Due to recent events in the Philippines political history, the ascendency of Duterte may come to no surprise. Since the overthrow of Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos in 1986. There have been a series of corrupt politicians in the seat of power that have either manipulated election results or interpreted constitutional laws to benefit their own agenda (Thompson, 2010).

Corruption within the Philippine government may largely be a result of Spanish and United States imperialism (Quimpo, 2009) however, current anger toward the political process may have begun in 2001 under the Presidency of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. She was elected following the popular overthrow of President Joseph Estrada. She immediately took office after serving as the Vice President (Hutchcroft, 2008). Shortly after her rise to power, Arroyo promised to put an end to many of the corrupt practices of the Estrada regime. She publicly discussed the moral decay of Philippine society and how she planned to put an end to this moral decline. The people would soon learn, however, that these were empty promises (Quimpo, 2009).

After seizing power, Arroyo reneged on her promises and filled major positions with officials long associated with Estrada. Graft and corruption continued throughout the following years, leading to a rise in opposition (Quimpo, 2009). Many of Estrada’s supporters protested her legitimacy, not realizing she had continued business as usual. When she ran for reelection in 2004, she ran a tight election against Fernando Poe Jr, close friend of Estrada, narrowly winning the Presidency. Curato (2017a) argued that this close election “exposed the endurance of populist appeal among voters” (p. 143). Much of the opposition claimed rampant election fraud. Corruption and graft continued throughout Arroyo’s second term. Once the term ended, Arroyo was arrested for the misuse of over $8 million (Whaley, 2012).

A long strand of corrupt Presidents made the election of 2010 an important aspect of the success and survival of the Philippines. In fact, the election of Benigno Aquino III may have been spurred by the rampant graft throughout the Arroyo presidency. Aquino ran on a good governance and economic development platform (Thompson, 2014). His reforms were supported by several organizations, including many people involved in the women’s movement (Mendoza, 2013).

While there was at least one scandal during the Aquino presidency, his popularity remained high. Due to constitutional term limits, Aquino could not run for reelection (Thompson, 2014). Aquino threw his support behind Manuel Roxas for the presidential election of 2016. This election cycle proved to be an unusual assortment of reformist and populist candidates fighting for the hearts of the populace. Several controversial candidates faced off against each other, leaving the field open for a populist candidate. Effectively, the sheer number of reformist candidates split the votes so that Rodrigo Duterte could ride in victoriously (Curato, 2017a).

The populist and nationalist sentiments in Philippine politics has long been apparent and has peaked its head once again. Why has the Philippines been so susceptible to populist and nationalist rhetoric and how is this related to geography? The purpose of this study is to give a detailed outline of populist and nationalist tendencies within the Duterte presidency and determine the source of national-populism.

Elements of National-Populism in the Philippines

Populist and nationalist leaders appeal to a group of people that feel ignored within the political process. This leads to the creation of an us-vs-them mentality, whereby one group is being subjugated by another group (Canovan, 1999). As Müller (2016) explained, populist leaders must follow three criteria in order to be considered a populist: (1) anti-elitist, (2) anti-pluralist, and (3) morally charged. The crossover of nationalist and populist sentiment today is largely driven by globalization. According to Brubaker (2017), current trends around the world are “not simply populist”, but they are “(with a few exceptions) national-populist” (p. 1191). This type of populism not only distinguishes between the ‘people’ and the ‘elites’, but also discerns between ‘us’ (insiders) and ‘them’ (outsiders). This rise in national-populism has been largely attributed to a growing economic divide throughout the global community (Azmanova, 2011; Stiglitz, 2018).

Populist style leadership in the Philippines is not a new phenomenon, but Rodrigo “Duterte’s style is a departure” from the norm (Curato, 2017a, p. 145). His brand of populist rhetoric has been compared to that of United States President Donald Trump. According to Brubaker (2017), Trump’s rhetorical style takes on a combination of both nationalist and populist philosophies. In his inaugural address, Trump stated “for too long, a small group in our nation’s Capital has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the cost. Washington flourished – but the people did not share in its wealth,” only later mentioning that “We’ve defended other nation’s borders while refusing to defend our own” (Trump, 2017). Both of these statements reflect the beliefs of a national-populist.

So, what does Trump’s inaugural address have to do with Rodrigo Duterte? Many scholars and journalists agree that Trump reflects both nationalist and populist sentiments (Brubaker, 2017; Lind, 2016), and the similarities between their style of national-populism provide an interesting comparison. These similarities, however, are in style not in views. According to Curato (2017a), both political personalities are putting on a virtual show and the people are their audience. This is further perpetuated through the use of social media. Further exploration of this relationship is beyond the scope of this study; however, their relationship is important to note, due to the former colonial status of the Philippines to the United States.

While there are some similarities between the two political figures, Duterte provides and interesting divergence from national-populist leaders around the world. Although he discussed unfair labor practices by the transnational elites (Curato, 2017a), Duterte’s campaign largely focused on the return of order. He called for harsh punishments for drug dealing and organized crime. He even threatened the dissolve the Philippine Congress if they did not follow his lead (Teehankee & Thompson, 2016). While on the campaign trail, he was not afraid to let his opinions about criminals be known. “You drug pushers, hold-up men and do-nothings, you better go out. Because I’d kill you” (Goldman, 2016).

Duterte has exemplified the characteristics of a national-populist through much of his campaign rhetoric and promises. According to Brubaker (2017), national-populists exist on both a vertical and horizontal scale (Figure 1). The national-populist perpetuates the existence of a divide between those who have power and those who do not, while also blaming the ills of the ‘in’ group on outsiders. To Duterte, corrupt politicians represent the elites that need to be handled. “If you are corrupt, I will fetch you using a helicopter to Manila and I will throw you out”. He expressed similar sentiments when he warned the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court that if he did not get what he wanted, he would declare martial law (Trimble, 2017). He also reflected regional attitudes toward the Manila elite when he called for the creation of a federal form of government (Teehankee, 2016).

The outsiders in Duterte’s case are China, United States, and the European Union. His public statements against the Chinese encroachment in the South China Sea presents a hardline stance against a perceived geopolitical threat, however his position has improved since his election (Teehankee & Thompson, 2016). He has taken a nationalist tone toward the United States, markedly different from previous administrations. In an attempt to show his support for China, he made a controversial statement in Beijing; “Your honours [sic], in this venue, I announce my separation from the United States” (Teehankee, 2016, p. 70).

Duterte’s comments toward the European Union may provide some insight as to his sentiments toward both the European Union and the United States. Outside criticism against Duterte has largely come from the European Union and the United Nations, claiming that his War on Drugs is causing mass casualties. He has countered these complaints by publicly shaming the European Union’s imperialist past (Teehankee, 2016). “It's easy to criticise [sic], it's easy to point out mistakes. My God, you trace your history. You also washed your hands with blood” (Morales & Dela Cruz, 2017).

With all of President Duterte’s fantastic quotes, his style of nationalism is slightly different than that of his contemporaries. European nationalism has been largely spawned by anti-European Union sentiments due to growing wealth inequality (Hopkin, 2017) and an increase in immigration from North Africa and the Middle East, leading to the rise of several politicians calling for the closing of borders to immigrants (Brubaker, 2017). Trump’s nationalistic rhetoric was along the same lines; however, he spoke of reducing immigration from Latin American countries as well (Steinberg, et al., 2017).

What makes Duterte different from others around the world is the type of nationalism he exemplifies. While others focus on immigration, Duterte focuses his attention on former imperial powers. This form of nationalism is directed toward a foreign policy viewpoint, not an economic perspective. He has publicly supported increased trade liberalization through bilateral deals with China, the United States, and the European Union (Teehankee, 2016).

Kymlicka (2002) argued that today there exists a different type of nationalism, termed liberal nationalism, by which cultures want to interact and share space with other groups but still retain their unique cultural traits. In an interview with Al Jazeera in November of 2017, Duterte commented on the mass migration of refuges to Europe stating, “They can always come here, and will be welcome here, until we are filled to the brim.” He later commented, “It’s all right. We will survive. I say send them to us. We will accept them. We will accept them. They are human beings.” (Petty, 2017) His opinions toward other cultures support the ideals of a liberal nationalist.

Duterte promised the Philippine people that he would respect the dignity of the Presidency and work with others in a more congenial manner (Curato, 2017a). However, national-populists rarely change their mindset once in office. Müller (2016) argued that populists immediately occupy the presidential office and begin to thwart potential enemies within the state apparatus. He also argued that the populist will either use the constitutional function of the government to remake it in their image or change it all together, claiming that it is the will of the people. According to Inglehart and Norris (2016), while populist leaders are popularly elected, once in office, they act with authoritarian fervor.

Beyond all of his campaign threats against perceived enemies, how has Duterte acted so far? Once in office, Duterte almost immediately reversed the previous administrations policies on China and the United States. He has focused on bilateral agreements, rather than multilateral agreements, toward China and has continued to strain relations with the United States (De Castro, 2017). While this does not fit the actions of a populist, it does fall in line with nationalist philosophy; the nation-state should broker deals on an individual basis rather than depend on multilateral neoliberal trade policies (Mayall, 1984).

Duterte was initially successful at getting the majority support that he wanted. While he only received 39% of the voting share (Teehankee & Thompson, 2016), after the election a super majority of the members of congress crossed over to his party, giving him a mandate to enact his platform. Surprisingly to the outside world, Duterte had an overwhelming trust rating of 91% of the voting population shortly after the election (Curato, 2017a). While the extent of his authoritarianism has yet to be seen, Duterte has received international condemnation for his extrajudicial killing of drug dealers and users (Quimpo, 2017). It has become so well known to the world community that Duterte himself had to admit his crimes. In a speech on September 26, 2018 at the Presidential Palace, Rodrigo Duterte admitted, “My only sin is the extrajudicial killings” (Villamor, 2018).

In both his presidential campaign and the first two years of his presidency, Rodrigo Duterte has seen great popularity from the Philippine people. This popularity follows an increase in authoritarian decisions such as the killing of drug dealers without a trial and international condemnation. His national-populist rhetoric did not stop with the start of his presidency. He has continued his version of national-populism, making him an anomaly amongst other national-populists. In the next section, I will discuss the major theories behind the rise in national-populism and determine where the Philippines fits within the scope of these theories.

Theoretical Framework

There has been much disagreement over the causes of rising national-populist sentiment around the world, making it a difficult topic to discuss on a national level. Inglehart and Norris (2016) outlined two theories regarding the rise of populism: the cultural backlash thesis and the economic inequality thesis. While both of these theories provide compelling reasoning, it is difficult to apply them to the national-populist movement in the Philippines.

The cultural backlash thesis finds its roots in what Inglehart (1977) called the ‘silent revolution’. This theory argues that Western countries are shifting from a materialistic culture, based on material wealth, to a quality of life centered culture. This has brought about a rise in multiculturalism and left-leaning political groups. Inglehart and Norris (2016) argued that this has caused political upheaval in Western Europe, and to a lesser extent the United States. Older, lesser educated, and rural members of these societies are currently fighting against these changes, leading to the rise of nationalist and populist leaders.

The economic thesis is not new; however, scholars have argued that globalization and a growing income gap has led to the rise of national-populist leaders like Marine Le Pen in France, Geert Wilder in the Netherlands, and Donald Trump in the United States (Stiglitz, 2018). Others have argued that movements against the European Union, such as Brexit, are largely due to economic inequality. Even issues regarding immigration have been spurred by the rise of cheap labor and reduction in manufacturing jobs (Hopkin, 2017).

These theories are not diametrically opposed, however. Other scholars have argued on a case study basis that populist and nationalist sentiments can be attributed to a combination of both cultural and economic concerns, especially in the European sphere (Hobolt, 2016). The major problem with these two theories is that some important geographic aspects have been overlooked. Mudde and Kaltwasser (2013) compared Latin American populism to that of Europe and found major differences between the two regions. There is an obvious sociocultural and geographic difference between these two regions; however, these studies ignore the completely unique form of national-populism that exists in the Philippines and other Southeast Asian countries.

Inglehart and Norris (2016) used data from a 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Study (CHES) to determine if party affiliation matched ideological leanings of those surveyed. The statistics were organized into a control group, control plus economic group, control plus cultural values group, combined model, and an interactions model. Logistic regression was performed and results showed that the best explanation of the rise of populism in Europe was due to xenophobia, a cultural affinity toward authoritarianism, and distrust of global government. The economic inequality model was significant to a lesser extent but failed to explain the rise of populism as well as the cultural model.

Analyzing the Data

Due to limited availability of survey data in the Philippines, this study cannot use the same statistical analysis, however, comparable data were available in order to draw some conclusions about the state of the national-populist government under Duterte’s leadership. Aggregated economic data were compiled from the World Bank and Knoema Corporation. Regional economic data were taken from the Philippine Statistics Authority. The pre-election survey data available for study was made possible by several surveys performed by the Social Weather Station, a research institute based out of the Philippines concerned with the social sciences (Mangahas, 2015), and the Manila Standard, a broadsheet newspaper located in the Philippines (Puno, 2018). All data are provided on tables located in the appendix.

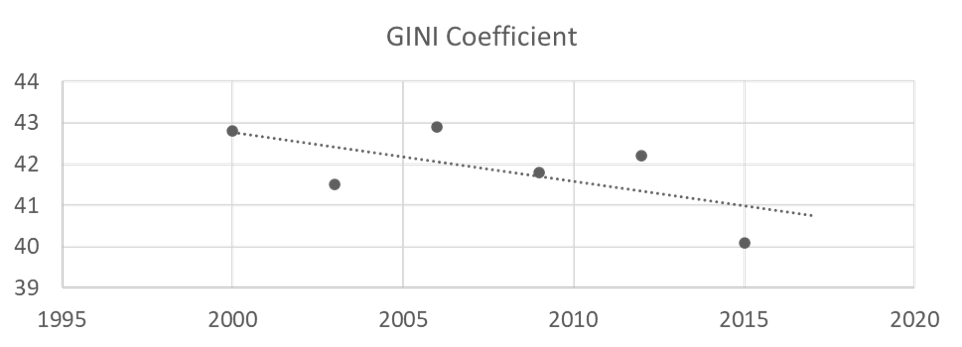

National economic data shows a reduction in poverty across the Philippines from 24.9% in 2003 to 21.6% in 2015 (Figure 2). The same can be said for the GINI coefficient. This statistic is based on the Lorenz Curve and calculates the distribution of income from the highest and lowest values on a scale of 0-100 (0 being an equal distribution of income; 100 being perfectly unequal) (World Bank, 2018). GINI coefficient variables show between 2000 and 2015 that income is becoming more equally distributed, although not at a qualitatively dramatic rate (Figure 3). In the year 2000, the Philippine GINI Coefficient was 42.8 and dropped to 40.1 by 2015. However, inequality did stagnate between 2003 and 2012, possibly due to economic recession. Growing resentment toward United States economic policy in the Philippines has largely been a result of this stagnating inequality. While some authors argue that the Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA) regime’s economic policy created rampant inequality (Bello, 2017). The GINI coefficient shows that inequality is significant but has dropped considerably since 2000. However, the GINI coefficient is not a perfect representation of life in the Philippines and may not accurately reflect wealth distribution on the micro-scale.

While unemployment rates dropped dramatically between 2002 and 2003, it has stagnated around 3 and 4 percent since 2004 (Figure 4). The gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate is not only high (its highest rate was 7.06% in 2013), it continues to rise with some variability over time (Figure 5). Some scholars have argued that neoliberal policies have plagued the middle class in the Philippines, leading to an ever-greater income gap (Curato, 2017c). However, this income gap cannot be represented in statistics like GDP and GDP growth rate (Stiglitz, 2017). In fact, judging by the GDP growth rate, GDP per capita, and gross national income (GNI) per capita (Table 2; Figure 6), the economic future looks bright for the Philippines.

Due to regional and sector differences, data were analyzed to reflect any discrepancies. The largest sector in the Philippine economy is mining and manufacturing, valued at $77.2 billion in 2016. Sales are a major sector as well, due to the growing tourism industry, valued at $54.5 billion in 2016. All major sectors have seen increases in value since 2005, with a minor decline between 2008 and 2009 due to recession (Figure 7). The major shortfall of this measure is aggregation. Data described here only describes the country as a whole and does not accurately depict the economic reality on the regional and/or micro level.

There is another issue, the increase in manufacturing and other like sectors in the Philippines is largely geographic and boosted by foreign direct investment (Makabenta, 2002), creating regional economic disparity (Clausen, 2010). An influx of capital to major urban regional centers boosted incomes dramatically and created a new middle class. However, middle class families in certain regional areas expressed their frustration in the 2016 presidential campaign (Teehankee, 2017). Regional GDP shows a consistent growth in income across all major regions between 2015 and 2017, however, some regions developed much quicker than others (Figure 8). The range of growth for the National Capital Region increased from $5.05 billion in 2015 to $6.02 billion in 2017, outpacing all other regions (Table 4). The National Capital Region, Calabarzon, and Central Luzon (all regionally situated around Manila) combined had a GDP of $9.79 billion while all of the other regions combined had a GDP of just $6.01 billion. This regional disparity, a geographic factor, played a major role in the election of Rodrigo Duterte (Figure 9).

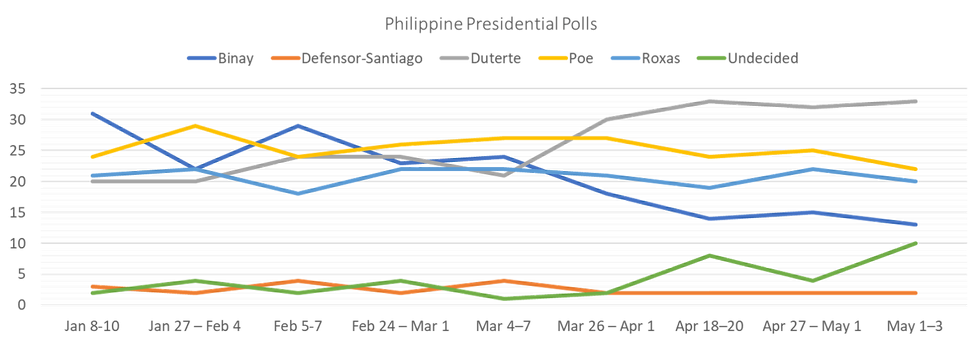

Polling data were collected and compiled showing expected results. In January 2016, prior to the election, Duterte was trailing in 4th place with 20% of the polled votes. His supported remained between 20-25% until the beginning of April. He saw a dramatic uptick in votes, sending him to the lead with 33% the week before the election (Table 7 and Figure 10). Duterte’s late rise in the pre-election polls sheds light on many unanswered questions. He went from a relatively unknown mayor of Davao to the leading candidate in the Philippine presidential race. His popularity was largely due to regional frustration of the voters, many of which felt his law and order style of management was what the Philippines needed (Teehankee, 2017).

Duterte’s largest support was in Mindanao, home to Davao. He held a consistent lead in this region. He carried 22-23% of the vote in the National Capital Region; combining both regions, Duterte was able to win the election (Figure 11). His support in Mindanao can be explained by his popularity during his time as Mayor of Davao. He promised to bring about peace in Mindanao if elected president and won large support amongst the Muslim population (Figure 13). Growing mistrust of Manila amongst the Mindanao people fit quite well with Duterte’s electoral campaign. He allied himself with the Moros and migrant settler population and promised to give power to the regional governments (Altez & Caday, 2017).

In order to determine if a relationship exists between income and voting pattern by region, spatial regression was performed between the percentage of votes for Duterte (dependent variable) and regional GDP (independent variable) using GeoDa version 1.4.6. Continuous second order queen contiguity weights were added due to strong spatial autocorrelation. Continuous queen contiguity weighting applies a weight of 1 to all polygons that share a border and corner (Figure 12); a 0 is given to all other polygons (O’Sullivan & Unwin, 2010).

The following formula was used in the spatially weighted regression analysis:

y_i=g(y,a)+Xb+e

e=h(e,c)+u

Where g and h are the weights, g(y,a) is the independent variable, and h(e,c) is the error term. Results show an r-squared of 0.59, a p-value of 0.017, and a positive linear relationship between the percentage of votes Duterte received and regional GDP. However, the slope for regional GDP was less than 0.0001, making the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable minor (Table 1). This relationship implies that as regional GDP increased, so did the percentage of votes that Duterte received. Because the coefficient for regional GDP is so low, however, this relationship is not powerful enough to warrant further exploration.

Table 1

Model Averaged Parameter Estimates of Regional GDP and percentage of votes given to Rodrigo Duterte. Weighted spatial regression model, continuous second order queen contiguity, spatial error method (sources: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2017; Panares, 2018. Generated using GeoDa 1.4.6).

The most remarkable aspect of the regional variability is the changes between pre-election polls and post-election satisfaction polls. According to pre-election polling, Duterte’s major support came from Mindanao, with the National Capital Region and Visayas coming in second. Post-election polls taken on various dates between September 2016 and September 2018, administered by Social Weather Station, show a slow decline in approval rating (Table 8 and Figure 14). While it is declining, his approval rating still remains high considering his two-year stint in office.

The most unusual aspect of the regional satisfaction polls is his approval rating in Mindanao. Since his election, his approval rating in a region that he promised so much, dropped from 66% in September 2016 to 40% in 2018. However, his approval in Manila remains high, 81% in September 2016 and 67% in September 2018. His approval rating in Mindanao has dropped more than any other region. During the election, Duterte promised that if he were elected that he would help to create a federalist system of government, giving more power to the regional governments (Cau, 2016). While he has pushed the Philippine Congress to pass constitutional reform, his federalist plans have largely been unsuccessful. Foreign investors have complained that Duterte has not taken the federalism issue seriously (Alegado & Calonzo, 2018).

Because federalist reforms have failed to pan out and Duterte has consolidated power in Manila, regional support for his policies have dropped in recent months. Duterte successfully tapped into the wishes of his supporters so that he could successfully win the Presidency. However, he has reversed himself on several major campaign promises (Ranada, 2018). National-populists often promise to give power back to the people, but once in office they consolidate power and remove political dissidents (Müller, 2016). Almost immediately after Duterte’s election, a large number of congressional members switched to his party, giving him a congressional super majority (Teehankee & Thompson, 2016). This consolidation of power around Manila may be part of the reason that he has lost support in Mindanao.

According pre-election polls of various social groups, the only major group that supported Duterte was the upper socio-economic class (ABC) (Figure 15). This is reflected in greater detail when looking at the breakdown of socio-economic polling data. Between January and February of 2016, polling data shows 27% and 30% support, respectively, among the wealthy and middle classes (Figure 16). According to Teehankee (2017) “the Duterte phenomenon was not a revolt of the poor but was a protest of the new middle class who suffered from a lack of public service” (p.52). This protest can be seen clearly in the polling data.

Further polling shows some interesting social aspects of Duterte’s success. His support within age groups was evenly distributed, however, he was preferred by 18% of ages 56 and older, 22% of ages 25-55 years, and 20% of ages 18-34 (Figure 15). His popularity amongst the middle-aged group was due in part to his support amongst middle-class merchants and those with something to lose. Male to female ratio is an interesting case. While a 5-point gender gap is relatively small, it does show that more men preferred Duterte than women.

Duterte’s popularity in rural and urban communities prior to the election was consistent, with 20% in rural areas and 21% in urban areas. His support in rural and impoverished communities was largely due to his grassroots campaigns, with major support from local businesses (Curato, 2017b). Duterte had major support from Muslims; 34% of Muslims supported him prior to the election (Figure 13) due to his time as mayor in a Davao, a region with a large Muslim population. Christians were more supportive of presidential candidate Grace Poe than any other candidate, but Duterte did get support from 25% of the members of Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ).

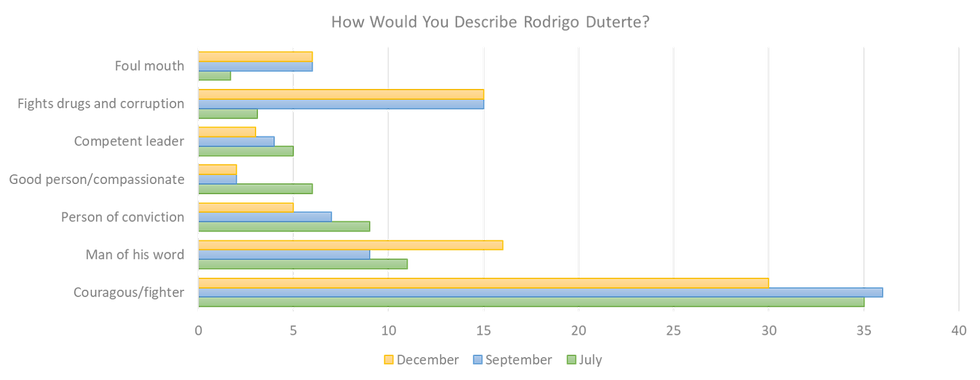

Between January 27 and February 4 of 2016, voters were surveyed and asked why they supported Duterte. These results provide valuable information on his popularity. While the reasons listed vary, results show that 86% of those polled said that they liked Duterte because of his disciplinarian and authoritative nature, as well as his anti-elitist platform. Only 13% supported him for more generic reasons such as liking his style of management (Figure 17). After the election, people were asked on three separate occasions to describe Duterte in one word. Not surprisingly, most people described him based on his authoritative style of governing, his war against crime, and his ability to keep his word (Figure 18).

National/regional economic and polling data provide some in-depth information on the political and economic climate in the Philippines prior to the presidential election of Rodrigo Duterte. This data does not completely conform to national-populist models used to describe Europe and the United States, however, there are some overlaps. The next section will use the data described in this section to provide a new theory explaining the rise of national-populism in the Philippines.

Discussion

Rodrigo Duterte easily fits within the sphere of a populist; however, he is does not check all the boxes when it comes to nationalism. For this reason, I must rework the definition of a national-populist as it related to Duterte. According to Müller (2016), populists are anti-elitist, anti-plural, and claim a moral responsibility to their leadership. Duterte spoke out against the central government of Manila and offered a federalist form of government as an alternative; a ploy to gain support from Mindanao and other regions far away from the National Capital Region. While Duterte has not stated unequivocally that he is anti-pluralist, he has insinuated that he is the only person that can effectively represent the people of Davao. He has said that he will reduce crime by using the “Davao model” (Chen, 2016) on a national level. This model of governance has been implemented as a moral backlash against crime and the elite’s control in Manila.

Economic Inequality Thesis

Does the election of Duterte fit the economic inequality thesis discussed by Inglehart and Norris (2016)? Unfortunately, the right type of data does not exist to perform the same calculations. However, there is enough data included in this paper to evaluate the economic inequality thesis as it relates to the Philippines. While there is a gap between the top and bottom income earners, this gap has been closing due in large part to industrialization. GDP, GDP per capita, and GNI per capita have all been increasing at a dramatic rate. On a national scale, the Philippines has become a booming newly industrializing country and attracted investment from around the world, however, regional data shows that this is not universally true across the entire country.

Duterte’s largest voting block was wealthy merchants and industrialists. Lower class voters generally supported Grace Poe with a plurality of votes. The spatially weighted regression analysis performed on regional voting patterns shows that there is a minor relationship between regional wealth and the percentage of votes for Duterte. He was favored by the wealthier class because he promised a pivot away from the United States and the EU; this would give more power to the local business and industrial elites. While this does not fit in with the economic inequality thesis, it is a nationalistic move for sure. For reasons states here, it can be concluded that the economic inequality thesis does not apply in the case of Rodrigo Duterte. More data is needed to perform a more complete analysis in the future.

Cultural Thesis

A quantitative analysis could not be performed with polling data due to the type of data gathered, however, some conclusions can be drawn regarding the cultural thesis. Duterte’s support from male voters lends some credence to this thesis, however, the discrepancy between male and female is not high enough to make a strong case either direction. He was largely supported by the Muslim populations but this was due to geographic factors, not cultural factors. There is a large Muslim population in his home region of Mindanao (Chen, 2016).

The most supportive evidence for the cultural thesis is the voter opinion polls performed in 2016 by the Manila Standard and Pulse Asia Research Inc. In both polls, voters described his presidency and personality based on strength of leadership, staying clear of economic and social issues. While this does lend credence to the cultural thesis, there is no information confirming a fear of immigrants or changing political landscape. According to Curato (2016c), Duterte is publicly a left-wing politician and supports socialist policies. Campbell (2016) argued that he has largely been supportive of gay marriage and is devoutly catholic. According to Chao (2016), he even offered immigrants and refugees from the Middle East and North Africa a home in the Philippines. Of course, Duterte’s father was a migrant settler and he largely supported these people in Mindanao (Altez & Caday, 2017).

Because of inconsistencies within the data, I have rejected the cultural thesis as well. These inconsistencies are largely due to his socially left-leaning ideologies. While Inglehart and Norris (2016) discuss the left-right paradigm in an economic heuristic model and a cultural value model, the cultural thesis does not fit well with Filipino Marxist populism exemplified by Rodrigo Duterte. Müller (2016) argued that populism does not always need to include “ethnic chauvinism” to be considered populism (p.25). Further data collection is needed in order to provide a more thorough investigation.

What About Geography?

Other causes for the rise of national-populism may be apparent but are often overlooked. Tolgyesi (2016) argued that geopolitical issues can play a major role in populist rhetoric and policy decisions. However, this analysis failed to provide a functional theory behind the development of nationalism in the countries surveyed. It is my contention that, while cultural issues and economic issues play a role in the rise of national-populism in the Philippines, geopolitics may present a more compelling reason behind the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte.

When Duterte proclaimed that he would ride a jet ski to the Spratly Islands and place the Philippine flag on the shore, he received some backlash. However, he was hailed by many supporters as a Filipino hero. He earned the nickname ‘Iron Fist’ because of the way he dealt with crime as mayor of Davao, but his tough stance against China’s encroachment on Philippine waters solidified this nickname. However, since his election, he has largely reversed his tough stance with China when he chose to pivot away from US trade influence (Westcott, 2018).

Many Philippine citizens have been concerned with the growing military presence of China near their borders, however, a more pressing issue is that of the United States. His crass relationship with the United States began when Duterte gave a speech condemning Barack Obama and declared that the Philippines was no longer a colony of the United States. He grew large support from the Philippine population when he blamed crime problems and economic instability on their historical and geopolitical relationship with the United States (Webb, 2017).

He held a similar stance with the EU. This public condemnation fits a national-populist tone: one man standing up against the elites in Manila and other foreign governments in order to protect his ‘people’ (Teehankee & Thompson, 2016). Duterte’s form of national-populism is in many ways a form all his own. He has gained wild popularity as a protector from foreign aggression and a crime fighting tough guy. Geopolitics and regionally motivated disparity are largely responsible for the rise of Rodrigo Duterte.

References

Alegado, S., & Calonzo, A. (2018). Duterte has grand ambitions to share Manila's wealth. Bloomberg. Retrieved October 11, 2018, from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-07-19/glaring-wealth-divide-pushes-duterte-toward-federalism-legacy

Altez, J. A. L., & Caday, K. A. (2017). The Mindanaoan president. In N. Curato (Ed.), A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on Rodrigo Duterte's Early Presidency (pp. 145-166). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Azmanova, A. (2011). After the Left–Right (Dis) continuum: Globalization and the Remaking of Europe's Ideological Geography. International Political Sociology, 5(4), 384-407.

Bello, W. (2017). Rodrigo Duterte: A fascist original. In N. Curato (Ed.), A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on Rodrigo Duterte's Early Presidency (pp. 77-91). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Brubaker, R. (2017). Between nationalism and civilizationism: the European populist moment in comparative perspective. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(8), 1191-1226.

Bruen, B. (2018). Pragmatism Over Political Theater. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 1, 2018, from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2018-07-30/commentary-italys-new-leaders-must-embrace-old-political-system-to-change-it

Campbell, C. (2016). People keep calling Rodrigo Duterte the Philippine Donald Trump. They're wrong. Time. Retrieved October 11, 2018, from http://time.com/4324098/rodrigo-duterte-philippines-president-donald-trump-human-rights-immigration/

Canovan, M. (1999). Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies, 47(1), 2-16.

Cau, E. (2016). Duterte, the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region conundrum and its implications. Asia Japan journal, (12), 79-97.

Chao, S. (2016). Duterte offers refugees a home in the Philippines. Al Jazeera. Retrieved October 11, 2018, from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/11/duterte-offers-refugees-home-philippines-161117073606596.html

Chen, A. (2016). When a populist demagogue takes power. The New Yorker. Retrieved October 15, 2018, from https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/11/21/when-a-populist-demagogue-takes-power

Clausen, A. (2010). Economic globalization and regional disparities in the Philippines. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 31(3), 299-316.

Curato, N. (2017a). Flirting with Authoritarian Fantasies? Rodrigo Duterte and the New Terms of Philippine Populism. Journal of Contemporary Asia,47(1), 142-153. doi:10.1080/00472336.2016.1239751

Curato, N. (2017b). Politics of anxiety, politics of hope: Penal populism and Duterte'. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs,35(3), 91-109.

Curato, N. (Ed.). (2017c) We need to talk about Rody. In A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on Rodrigo Duterte's Early Presidency (pp. 1-36). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

De Castro, C. (2016). The early Duterte Presidency in the Philippines. Journal of Current Southeast Asia Affairs,35(3), 139-159.

Goldman, R. (2016). Rodrigo Duterte’s Most Contentious Quotations. The New York Times. Retrieved October 3, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/09/30/world/asia/rodrigo-duterte-quotes-hitler-whore-philippines.html

Heydarian, R. J. (2018). Understanding Duterte’s mind-boggling rise to power. The Washington Post. Retrieved October 1, 2018, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/theworldpost/wp/2018/03/20/duterte/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.4556fe90d90d

Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259-1277.

Hopkin, J. (2017). When Polanyi met Farage: Market fundamentalism, economic nationalism, and Britain’s exit from the European Union. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19(3), 465-478.

Hutchcroft, P. D. (2008). The Arroyo imbroglio in the Philippines. Journal of Democracy, 19(1), 141-155.

Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution: Changing values and political styles among western publics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2016). Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic have-nots and cultural backlash. SSRN Electronic Journal, 1-52. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2818659

Knoema Corporation. (2018). Philippines. Retrieved October 5, 2018, from https://knoema.com/atlas/Philippines/topics/Economy.

Kymlicka, W. (2002). From Enlightenment Cosmopolitanism to Liberal Nationalism. In Politics in the Vernacular: Nationalism, Multiculturalism, and Citizenship (pp. 203-220). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lind, M. (2016). Donald Trump, the Perfect Populist: Why the GOP front-runner has far broader appeal than his predecessors going back to George Wallace. Politico Magazine. Retrieved October 3, 2018, from https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2016/03/donald-trump-the-perfect-populist-213697

Makabenta, M. P. (2002). FDI location and special economic zones in the Philippines. Review of Urban & Regional Development Studies, 14(1), 59-77.

Mangahas, M. K. (2015). Social Weather Station: About SWS. Retrieved October 9, 2018, from https://www.sws.org.ph/swsmain/aboutpg/?pnldisp=10

Manila Standard. (2016). Duterte surges in Standard Poll. Retrieved October 9, 2018, from http://manilastandard.net/the-standard-poll/202944/the-standard-poll-latest-results-march-26-april-1-2016-.html

Mansour, R., & Khatib, L. (2018). An emerging populism is sweeping the Middle East. The Washington Post. Retrieved October 1, 2018, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2018/07/11/what-populist-success-in-iraq-and-lebanon-says-about-todays-middle-east/?utm_term=.c6f1aaa12a20

Mayall, J. (1984). Reflections on the ‘new’ economic nationalism. Review of International Studies, 10(4), 313-321.

Mendoza, D. J. (2013). Engaging the state, challenging the church: The women’s movement and policy reforms in the Philippines (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). City University of Hong Kong. Retrieved October 2, 2018, from http://lbms03.cityu.edu.hk/theses/abt/phd-ais-b46934054a.pdf

Molloy, D. (2018). What is populism, and what does the term actually mean? BBC. Retrieved October 1, 2018, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-43301423

Morales, N. J., & Dela Cruz, E. (2017). EU are ‘sons of bitches’, says Philippines President. The Independent. Retrieved October 3, 2018, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/eu-sons-of-bitches-rodrigo-duterte-philippines-president-hypocrisy-war-on-drugs-a7647581.html

Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2013). Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: Comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition, 48(2), 147-174.

Müller, J. (2016). What is Populism? Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

O’Sullivan, D., & Unwin, D. (2010). Geographic Information Analysis (Second ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

Panares, J. P. (2016). Closer than ever. Manila Standard. Retrieved October 9, 2018, from http://manilastandard.net/news/headlines/201088/closer-than-ever.html

Panares, J. P., & Bencito, J. P. (2016). Marcos still up, but Leni rallies. Manila Standard. Retrieved October 9, 2018, from http://manilastandard.net/news/headlines/204993/marcos-still-up-but-leni-rallies.html

Panares, J. P., & Ramos-Araneta, M. (2016). Poe keeps lead in Laylo survey. Manila Standard. Retrieved October 9, 2018, from http://manilastandard.net/news/headlines/198854/poe-keeps-lead-in-laylo-survey.html

Petty, M. (2017). Duterte says Philippines would welcome refugees: 'They can always come here.' Reuters. Retrieved October 3, 2018, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-duterte-idUSKBN13D0DD

Philippine Statistics Authority. (2017). GRDP Tables. Unpublished raw data from https://psa.gov.ph/regional-accounts/grdp/data-and-charts

PulseAsia Research Inc. (2016). Ulat ng Bayan. Retrieved October 10, 2018, from http://www.pulseasia.ph/databank/ulat-ng-bayan/

Puno, R. (2018). About Manila Standard. Manila Standard. Retrieved October 9, 2018, from http://manilastandard.net/about-us.html http://manilastandard.net/about-us.html

Quimpo, N. G. (2009). The Philippines: predatory regime, growing authoritarian features. The Pacific Review, 22(3), 335-353.

Quimpo, N. G. (2017). Duterte's "war on drugs": The securitization of illegal drugs and the return of national boss rule. In N. Curato (Ed.), A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on Rodrigo Duterte's Early Presidency (pp. 145-166). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Ranada, P. (2018). Two years of Duterte: Broken and fulfilled promises. Rappler. Retrieved October 11, 2018, from 205255-duterte-two-years-as-president-broken-fulfilled-promises

Rauhala, E. (2016). Rise of Philippines Duterte Stirs Uncertainty in the South China Sea. The Washington Post. Retrieved October 2, 2018, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/rise-of-philippines-duterte-stirs-up-uncertainty-in-the-south-china-sea/2016/05/10/d75102e2-1621-11e6-971a-dadf9ab18869_story.html?utm_term=.6aa6463b6c29

Social Weather Station (2017). The 2017 SWS Survey Review (Publication). Retrieved October 5, 2018, from Social Weather Station website: https://www.sws.org.ph/downloads/publications/2017%20SWS%20Survey%20Review_March%2017%20PSSC.pdf

Social Weather Station (2018). The 2018 SWS Survey Review Net satisfaction rating of the National Administration a “Very Good” +50. Retrieved October 5, 2018, from Social Weather Station website: https://www.sws.org.ph/swsmain/artcldisppage/?artcsyscode=ART-20181005230110

Steinberg, P. E., Page, S., Dittmer, J., Gökariksel, B., Smith, S., Ingram, A., & Koch, N. (2017). Reassessing the Trump presidency, one year on. Political Geography, 62, 207-215.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2018). Globalization and its Discontents Revisited: Anti-Globalization in the Era of Trump. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Teehankee, J. C. (2017). Was Duterte’s rise inevitable. In N. Curato (Ed.), A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on Rodrigo Duterte's Early Presidency (pp. 37-56). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Teehankee, J. C., & Thompson, M. R. (2016). Electing a strongman. Journal of Democracy, 27(4), 125-134.

Thompson, M. R. (2010). Reformism vs. Populism in the Philippines. Journal of Democracy,21(4), 154-168. doi:10.1353/jod.2010.0002

Thompson, M. R. (2014). The Politics Philippine Presidents Make: Presidential-Style, Patronage-Based, or Regime Relational? Critical Asian Studies, 46(3), 433-460.

Tolgyesi, B. (2016). The role of populist parties in the geopolitical discourse in Lithuania (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Tartu. Retrieved October 1, 2018, from http://dspace.ut.ee/bitstream/handle/10062/53958/tolgyesi_beatrix_ma_2016.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y

Trimble, M. (2017). Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte's 9 Most Controversial Quotes. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved October 3, 2018, from https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/slideshows/philippine-president-rodrigo-dutertes-9-most-controversial-quotes

Trump, D. J. (2017). Remarks of President Donald J. Trump - as Prepared for the Inaugural Address. Speech presented at Inaugural Address in 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington DC. Retrieved October 3, 2018, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/the-inaugural-address/.

Villamor, F. (2018). Duterte Says, ‘My Only Sin Is the Extrajudicial Killings’. The New York Times. Retrieved October 4, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/27/world/asia/rodrigo-duterte-philippines-drug-war.html?rref=collection/timestopic/Philippines&action=click&contentCollection=world®ion=stream&module=stream_unit&version=latest&contentPlacement=1&pgtype=collection

Webb, A. (2017). Hiding the looking glass: Duterte and the legacy of American imperialism. In N. Curato (Ed.), A Duterte Reader: Critical Essays on Rodrigo Duterte's Early Presidency (pp. 127-144). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Westcott, B. (2018). Beijing should 'temper' its behavior in the South China Sea, Duterte says. CNN. Retrieved October 15, 2018, from https://www.cnn.com/2018/08/15/asia/duterte-china-south-china-sea-intl/index.html

Westlind, D. (1996). The Politics of Popular Identity: Understanding Recent Populist Movements in Sweden and the United States (Lund political studies, 89). Lund, Sweden: Lund University Press.

Whaley, F. (2012). Philippines Ex-President Is Arrested in Hospital on New Charges. The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2018, from https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/05/world/asia/philippines-ex-president-arrested-in-hospital-on-new-charges.html

World Bank. (2018). LAC Equity Lab: Income Inequality - Income Distribution. Retrieved October 9, 2018, from http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/lac-equity-lab1/income-inequality/income-distribution

World Bank. (2018). Philippines. Retrieved October 5, 2018, from https://data.worldbank.org/country/philippines.

Comments